Opioid use has been on the rise for over a decade, correlating to an increase in overdose and overdose deaths among opioid users, most publicized in the outpatient setting.i Overdose can occur in a variety of ways such as unintentional ingestion by children or concomitant ingestion of single or multiple therapeutic doses of opioids with or without several sedating medications, either intentionally or inadvertently.ii

These adverse events are not limited to the outpatient setting. In the hospital setting, it has been found that most adverse events are a result of drug-drug interactions, most commonly between opioids, benzodiazepines, and/or cardiac medications.iii Best practices in the healthcare setting recommend avoiding using both medications together except in cases where patients are undergoing surgical procedures or in palliative care.

Documenting the Increased Risk

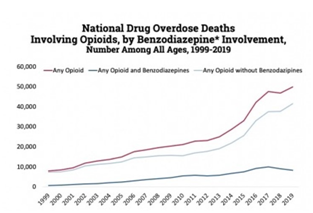

Among deaths with drug overdose as the underlying cause, the benzodiazepine category was determined by the T402.2 KD-10 multiple cause-of-death code, as shown in the graphic below. Among deaths with drug overdose as the underlying cause, the benzodiazepine category was determined by the T402.2 KD-10 multiple cause-of-death code, as shown in the graphic below.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Multiple Cause of Death 1999-2019 on CDC Wonder Online Database, released 12/2020.

Recent publications have documented the following in the healthcare environment:

“An association between preoperative opioid and benzodiazepine use and postoperative mortality and persistent postoperative opioid consumption in noncardiac surgery.”iv

“Concomitant opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions even for legitimate reasons should be strictly monitored, and continuous prescriber education as well as competency improvement and assessment may play an important role in ensuring patient safety." v

“Older adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are at substantially increased risk for medication-related adverse events from dual opioid and benzodiazepine use.” vi

“Policy interventions should focus on preventing concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use in the first place instead of reducing the length of concurrent use.” vii

“500-bed academic urban tertiary-care hospital: Composite of intensive care unit transfer or ward cardiac arrest: Opioids were associated with increased risk for clinical deterioration in the six hours after administration. Benzodiazepines were associated with even higher risk.” viii

Changing Regulatory Standards

In the intensive care unit, opioids and benzodiazepines are commonly given in conjunction with one another for sedation, muscle relaxation, and anxiolytic effects.ix ,x However, concurrent use of benzodiazepines and opioids may put patients at greater risk for potentially fatal overdose at both prescribed and greater than prescribed doses.

As a result of current data, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) xi is adding a “safe use of opioids” as a core measure in FY23 in order to flag one or more opioids and/or benzodiazepines as clinical quality measures.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advise against the concomitant use of benzodiazepines and opioids, whenever possible.xii

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a Boxed Warning advising on the risk of respiratory suppression (i.e., slowed or difficulty breathing) and death due to co-prescribing of opioids with CNS depressants, including benzodiazepines.xiii, xiv, xv

In 2014, the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, on behalf of the Federal Interagency Steering Committee for Adverse Drug Events, released the National Action Plan for Adverse Drug Event Prevention, which includes a focus on opioids and risks for accidental overdoses, oversedation, and respiratory depression. xvi

Best Practices

As standards become mandatory for continued accreditation, hospital and health system leaders are challenged with meeting the standard in a clinically meaningful way without overresponding and creating unforeseen side effects. It is best to establish the highest level of patient care that happens to meet the standard as opposed to focusing solely on “checking the box.”

In addition, as healthcare research produces results and revised methods of treatment and care for patients, there is a substantial gap between the healthcare that the patients receive and the recommended practice. This is known as the research-practice gap, evidence-practice gap, or knowing-doing gap and is as much as 17 years.xvii

Although there are instances when opioids and benzodiazepines can be appropriately used together, concurrent use outside of these indications should be limited. Despite an appropriate indication, the safety considerations of dual use must be outweighed by the benefits. Co-prescribing of opioid and benzodiazepine may be appropriate for those treated for pain palliation and oncologic diagnoses; muscle spasm secondary to spasticity associated with paraplegia, muscle spasm not responsive to any other antispasmodic therapy, and alcohol withdrawal protocol. Beyond the scope of finite clinical indications, the concomitant use of benzodiazepines and medication-assisted therapy to treat opioid addiction also requires further examination.

Recommendations

In order to avoid adverse patient outcomes and avoid overcorrection by regulators, consider the following:

- Develop and implement drug use criteria, in concert with stakeholders and healthcare teams, and revise order sets that contain both opioids and benzodiazepines.

- Develop structural and process of care indicators to elicit best practices and reduce harm for your patients.

i Warnings unheeded: The risks of prescribing opioids and benzodiazepines [homepage on the Internet]. International Association for the Study of Pain. 2015 November [cited 6/6/2017]. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/files/Content/ContentFolders/Publications2/PainClinicalUpdates/Archives/pcu_vol23_no6_nov2015.pdf.

ii Chapter 10: Clinical toxicology. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM, editors. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Education; 2014.

iii Safe use of opioids in hospitals [homepage on the Internet]. The Joint Commission. 2012 8 August [cited 7/13/2016]. Available from: https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_49_opioids_8_2_12_final.pdf.

iv JAMA Surg. 2019 Aug; 154(8): e191652.

v Pain Research and Management Volume 2019, Article ID 3865924.

vi AnnalsATS Volume 16 Number 10; October 2019.

vii JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(2):e180919.

viii J Hospital Med. 2017 June; 12(6): 428-434.

ix Gudin JA, Mogali S, Jones JD, Comer SD. Risks, management, and monitoring of combination opioid, benzodiazepines, and/or alcohol use. Postgrad Med. 2013 Jul;125(4):115-30.

x Jarman A, Duke G, Reade M, Casamento A. The association between sedation practices and duration of mechanical ventilation in intensive care. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2013 May;41(3):311-5.

xi https://www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Story-Page/prescribing-opioids. Accessed 9.01.21.

xii Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain--united states, 2016. JAMA. 2016 Apr 19;315(15):1624-45.

xiii Drug safety and availability > FDA drug safety communication: FDA warns about serious risks and death when combining opioid pain or cough medicines with benzodiazepines; requires its strongest warning [homepage on the Internet]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2016 31 August [cited 6/6/2017]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm518473.htm.

xiv Jones CM, McAninch JK. Emergency department visits and overdose deaths from combined use of opioids and benzodiazepines. Am J Prev Med. 2015 Oct;49(4):493-501.

xv Park TW, Saitz R, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA, Bohnert AS. Benzodiazepine prescribing patterns and deaths from drug overdose among US veterans receiving opioid analgesics: Case-cohort study. BMJ. 2015 Jun 10;350:h2698.

xvi National action plan for adverse drug event prevention [homepage on the Internet]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2014 [cited 6/6/2017]. Available from: https://health.gov/hcq/pdfs/ade-action-plan-508c.pdf.

xvii Morris et al. J R Soc Med 2011: 104: 510-520. Kristensen et al. BMC Health Services Research (2016) 16:48

All Posts

All Posts